XXIII

IN THEIR OWN WAY

Through the chinks in the logs, where the daubing had dropped out, Smith watched the lights in the ranch-house. He relieved the tedium of the hours by trying to imagine what was going on inside, and in each picture Dora was the central figure. Now, he told himself, she was wiping the dishes for Ling, and teaching him English, as she often did; and when she had finished she would bring her portfolio into the dining-room and write home the exciting events of the day. He wondered what had “ailed” the Indian woman, that she should die so suddenly; but it was immaterial, since she was dead. He knew that Susie would sit by her mother; probably in the chair with the cushion of goose-feathers. It was his favorite chair, though it went over backwards when he rocked too hard. Ralston—curse him!—was sitting on one of the benches outside the bunk-house, telling the grub-liners of Smith’s capture, and the bug-hunter was making notes of the story in his journal. But, alas! as is usual with the pictures one conjures, nothing at all took place as Smith fancied.

When all the lights, save the one in the living-room, had gone out, there was nothing to divert his thoughts. Babe, who was on guard outside, refused to converse with him, and he finally lay down, only to toss restlessly upon the blankets. The night seemed unusually still and the stillness made him nervous; even the sound of Babe’s back rubbing against the door when he shifted his position was company. Smith’s uneasiness was unlike him, and he wondered at it, while unable to conquer it. It must have been nearly midnight when, staring into the darkness with sleepless eyes, he felt, rather than heard, something move outside. It came from the rear, and Babe was at the door for only a moment before he had struck a match on a log to light a cigarette. The sound was so slight that only a trained ear like Smith’s would have detected it.

It had sounded like the scraping of the leg of an overall against a sage-brush, and yet it was so trifling, so indistinct, that a field mouse might have made it. But somehow Smith knew, he was sure, that something human had caused it; and as he listened for a recurrence of the sound, the conviction grew upon him that there was movement and life outside. He was convinced that something was going to happen.

His judgment told him that the prowlers were more likely to be enemies than friends—he was in the enemies’ country. But, on the other hand, there was always the chance that unexpected help had arrived. Smith still believed in his luck. The grub-liners might come to his rescue, or “the boys,” who had been waiting at the rendezvous, might have learned in some unexpected way what had befallen him. Even if they were his enemies, they would first be obliged to overpower Babe, and, he told himself, in the “ruckus” he might somehow escape.

But even as he argued the question pro and con, unable to decide whether or not to warn Babe, a stifled exclamation and the thud of a heavy body against the door told him that it had been answered for him. Wide-eyed, breathless, his nerves at a tension, his heart pounding in his breast, he interpreted the sounds which followed as correctly as if he had been an eye-witness to the scene.

He could hear Babe’s heels strike the ground as he kicked and threshed, and the inarticulate epithets told Smith that his guard was gagged. He knew, too, that the attack was made by more than two men, for Babe was a young Hercules in strength.

Were they friends or foes? Were they Bar C cowpunchers come to take the law into their own hands, or were they his hoped-for rescuers? The suspense sent the perspiration out in beads on Smith’s forehead, and he wiped his moist face with his shirt-sleeve. Then he heard the shoulders against the door, the heavy breathing, the strain of muscles, and the creaking timber. It crashed in, and for a second Smith’s heart ceased to beat. He sniffed—and he knew! He smelled buckskin and the smoke of tepees. He spoke a word or two in their own tongue. They laughed softly, without answering. From instinct, he backed into a corner, and they groped for him in the darkness.

“The rat is hiding. Shall we get the cat?” The voice was Bear Chief’s.

Running Rabbit spoke as he struck a match.

“Come out, white man. It is too hot in here for you.”

Smith recovered himself, and said as he stepped forward:

“I am ready, friends.”

They tied his hands and pushed him into the open air. Babe squirmed in impotent rage as he passed. Dark shadows were gliding in and out of the stable and corrals, and when they led him to a saddled horse they motioned him to mount. He did so, and they tied his feet under the horse’s belly, his wrists to the saddle-horn. Seeing the thickness of the rope, he jested:

“Friends, I am not an ox.”

“If you were,” Yellow Bird answered, “there would be fresh meat to-morrow.”

There were other Indians waiting on their horses, deep in the gloom of the willows, and when the three whom Smith recognized were in the saddle they led the way to the creek, and the others fell in behind. They followed the stream for some distance, that they might leave no tracks, and there was no sound but the splashing and floundering of the horses as they slipped on the moss-covered rocks of the creek-bed.

Smith showed no fear or curiosity—he knew Indians too well to do either. His stoicism was theirs under similar circumstances. Had they been of his own race, his hope would have lain in throwing himself upon their mercy; for twice the instinctive sympathy of the white man for the under dog, for the individual who fights against overwhelming odds, had saved his life; but no such tactics would avail him now.

His hope lay in playing upon their superstitions and weaknesses; in winning their admiration, if possible; and in devising means by which to gain time. He knew that as soon as his absence was discovered an effort would be made to rescue him. He found some little comfort, too, in telling himself that these reservation Indians, broken in spirit by the white man’s laws and restrictions, were not the Indians of the old days on the Big Muddy and the Yellowstone. The fear of the white man’s vengeance would keep them from going too far. And so, as he rode, his hopes rose gradually; his confidence, to a degree, returned; and he even began to have a kind of curiosity as to what form their attempted revenge would take.

The slowness of their progress down the creek-bed had given him satisfaction, but once they left the water, there was no cause for congratulation as they quirted their horses at a breakneck speed over rocks and gullies in the direction of the Bad Lands. He could see that they had some definite destination, for when the horses veered somewhat to the south, Running Rabbit motioned them northward.

“He was there yesterday; Running Rabbit knows,” said Bear Chief, in answer to an Indian’s question; and Smith, listening, wondered where “there” might be, and what it was that Running Rabbit knew.

He asked himself if it could be that they were taking him to some desert spring, where they meant to tie him to die of thirst in sight of water. The alkali plain held many forms of torture, as he knew.

His captors did not taunt or insult him. They rode too hard, they were too much in earnest, to take the time for byplay. It was evident to Smith that they feared pursuit, and were anxious to reach their objective point before the sun rose. He knew this from the manner in which they watched the east.

Somehow, as the miles sped under their horses’ feet, the ride became more and more unreal to Smith. The moon, big, glorious, and late in rising, silvered the desert with its white light until they looked to be riding into an ocean. It made Smith think of the Big Water, by moonlight, over there on the Sundown slope. Even the lean, dark figures riding beside him seemed a part of a dream; and Dora, when he thought of her, was shadowy, unreal. He had a strange feeling that he was galloping, galloping out of her life.

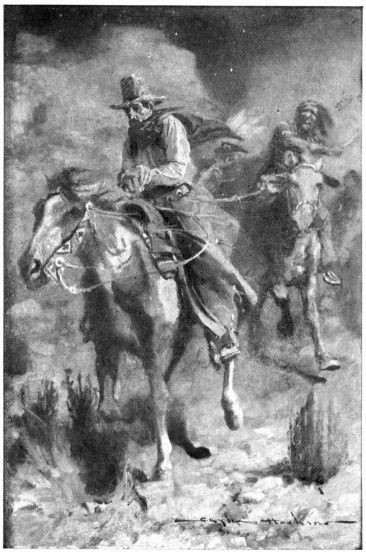

THEY QUIRTED THEIR HORSES AT BREAKNECK SPEED IN THE DIRECTION OF THE BAD LANDS.

There were times when he felt as if he were floating. His sensations were like the hallucinations of fever, and then he would find himself called back to a realization of facts by the swish of leather thongs on a horse’s flank, or some smothered, half-uttered imprecation when a horse stumbled. The air of the coming morning fanned his cheeks, its coolness stimulated him, and something of the fairy-like beauty of the white world around him impressed even Smith.

They had left the flatter country behind them, and were riding among hills and limestone cliffs, Running Rabbit winding in and out with the certainty of one on familiar ground. The way was rough, and they slackened their pace, riding one behind the other, Indian file.

Running Rabbit reined in where the moonlight turned a limestone hill to silver, and threw up his hand to halt.

He untied the rope which bound Smith’s hands and feet.

“You can’t coil a rope no more nor a gopher,” said Smith, watching him.

“The white man does many things better than the Indian.” Running Rabbit went on coiling the rope.

He motioned Smith to follow, and led the way on foot.

“I dotes on these moonlight picnics,” said Smith sardonically, as he panted up the steep hills, his high-heeled boots clattering among the rocks in contrast to the silent footsteps of the Indian’s moccasined feet.

Running Rabbit stopped where the limestone hill had cracked, leaving a crevice wide at the top and shallowing at the bottom.

“This is a good place for a white man who coils a rope so well, to rest,” he said, and seated himself near the edge of the crevice, motioning Smith to be seated also.

“Or for white men who shoot old Indians in the back to think about what they have done.” Yellow Bird joined them.

“Or for smart thieves to tell where they left their stolen horses.” Bear Chief dropped cross-legged near them.

“Or for those whose forked tongue talks love to two women at once to use it for himself.” The voice was sneering.

“Smith, you’re up against it!” the prisoner said to himself.

As the others came up the hill, they enlarged the half-circle which now faced him. Recovering himself, he eyed them indifferently, one by one.

“I have enemies, friends,” he said.

“White Antelope had no enemies,” Yellow Bird replied.

“The Indian woman had no enemies,” said Running Rabbit.

“It is our friends who steal our horses”—Bear Chief’s voice was even and unemotional.

Their behavior puzzled Smith. They seemed now to be in no hurry. Without gibes or jeers, they sat as if waiting for something or somebody. What was it? He asked himself the question over and over again. They listened with interest to the stories of his prowess and adventures. He flattered them collectively and individually, and they responded sometimes in praise as fulsome as has own. All the knowledge, the tact, the wit, of which he was possessed, he used to gain time. If only he could hold them until the sun rose. But why had they brought him there? With all his adroitness and subtlety, he could get no inkling of their intentions. The suspense got on Smith’s nerves, though he gave no outward sign. The first gray light of morning came, and still they waited. The east flamed.

“It will be hot to-day,” said Running Rabbit. “The sky is red.”

Then the sun showed itself, glowing like a red-hot stove-lid shoved above the horizon.

In silence they watched the coming day.

“This limestone draws the heat,” said Smith, and he laid aside his coat. “But it suits me. I hates to be chilly.”

Bear Chief stood up, and they all arose.

“You are like us—you like the sun. It is warm; it is good. Look at it. Look long time, white man!”

There was something ominous in his tone, and Smith moistened his short upper lip with the tip of his tongue.

“Over there is the ranch where the white woman lives. Look—look long time, white man!” He swung his gaunt arm to the west.

“You make the big talk, Injun,” sneered Smith, but his mouth was dry.

“Up there is the sky where the clouds send messages, where the sun shines to warm us and the moon to light us. There’s antelope over there in the foothills, and elk in the mountains, and sheep on the peaks. You like to hunt, white man, same as us. Look long time on all—for you will never see it again!”

The sun rose higher and hotter while the Indian talked. He had not finished speaking when Smith said:

“God!”

A look of indescribable horror was on his face. His skin had yellowed, and he stared into the crevice at his feet. Now he understood! He knew why they waited on the limestone hill! An odor, scarcely perceptible as yet, but which, faint as it was, sickened him, told him his fate. It was the unmistakable odor of rattlesnakes!

The crevice below was a breeding-place, a rattlesnakes’ den. Smith had seen such places often, and the stench which came from them when the sun was hot was like nothing else in the world. The recollection alone was almost enough to nauseate him, and he always had ridden a wide circle at the first whiff.

His aversion for snakes was like a pre-natal mark. He avoided cowpunchers who wore rattlesnake bands on their hats or stretched the skin over the edge of the cantle of their saddles. He always slept with a hair rope around his blankets when he spent a night in the open. He would not sit in a room where snake-rattles decorated the parlor mantel or the organ. A curiosity as to how they had learned his peculiarity crept through the paralyzing horror which numbed him, and as if in answer the scene in the dining-room of the ranch rose before him. “I hates snakes and mouse-traps goin’ off,” he had said. Yes, he remembered.

The Indians looked at his yellow skin and at his eyes in which the horror stayed, and laughed. He did not struggle when they stood him, mute, upon his feet and bound him, for Smith knew Indians. His lips and chin trembled; his throat, dry and contracted, made a clicking sound when he swallowed. His knees shook, and he had no power to control the twitching muscles of his arms and legs.

“He dances,” said Yellow Bird.

As the sun rose higher and streamed into the crevice, the overpowering odor increased with the heat. The yellow of Smith’s skin took on a greenish tinge.

“Ugh!” An Indian laid his hand upon his stomach. “Me sick!”

A bit of limestone fell into the crevice and bounded from one shelf of rock to the other. Upon each ledge a nest of rattlesnakes basked in the sun, and a chorus of hisses followed the fall of the stone.

“They sing! Their voices are strong to-day,” said Running Rabbit.

The Indians threw Smith upon the edge of the crevice, face downward, so that he could look below. With his staring, bloodshot eyes he saw them all—dozens of them—a hundred or more! Crawling on the shelves and in the bottom, writhing, wriggling, hissing, coiled to strike! Every marking, every shading, every size—Smith saw them all with his bulging, fascinated eyes. The Indians stoned them until a forked tongue darted from every mouth and every wicked eye flamed red.

The thick rope was tied under Smith’s arms, and a noose thrown over a huge rock. They shoved him over the edge—slowly—looking at him and each other, laughing a little at the sound of reptile fury from below. It was the end. Smith’s eyes opened before they let him drop, and his lips drew back from his white, slightly protruding teeth. They thought he meant to beg at last, and, rejoicing, waited. He looked like a coyote, a coyote when its ribs are crushed, its legs broken; when its eyes are blurred with the death film, and its mouth drips blood. He gathered himself—he was all but fainting—and threw back his head, looking at Bear Chief. He snarled—there was no tenderness in his voice when he gave the message:

“Tell her, you damned Injuns—tell the Schoolmarm I died game, me—Smith!”