XXI

THE MURDERER OF WHITE ANTELOPE

It was nearly dusk, and Ralston was only a few hundred yards from the Bar C gate, when he met Babe, highly perfumed and with his hair suspiciously slick, coming out. Babe’s look of disappointment upon seeing him was not flattering, but Ralston ignored it in his own delight at the meeting.

“What was your rush? I was just goin’ over to see you,” was Babe’s glum greeting.

“And I’m here to see you,” Ralston returned, “but I forgot to perfume myself and tallow my hair.”

“Aw-w-w,” rumbled Babe, sheepishly. “What’d you want?”

“You know what I’m in the country for?”

Babe nodded.

“I’ve located my man, and he’s going to drive off a big bunch to-night. There’s two of them in fact, and I’ll need help. Are you game for it?”

“Oh, mamma!” Babe rolled his eyes in ecstasy.

“He has a horror of doing time,” Ralston went on, “and if he has any show at all, he’s going to put up a hard fight. I’d like the satisfaction of bringing them both in, single-handed, but it isn’t fair to the Colonel to take any chances of their getting away.”

“Who is it?”

“Smith.”

“That bastard with his teeth stickin’ out?”

Ralston laughed assent.

“Pickin’s!” cried Babe, with gusto. “I’d like to kill that feller every mornin’ before breakfast. Will I go? Will I? Will I?” Babe’s crescendo ended in a joyous whoop of exultation. “Wait till I ride back and tell the Colonel, and git my ca’tridge belt. I take it off of an evenin’ these tranquil times.”

Ralston turned his horse and started back, so engrossed in thoughts of the work ahead of him that it was not until Babe overtook him that he remembered he had forgotten to ask Babe’s business with him.

“Well, I guess the old Colonel was tickled when he heard you’d spotted the rustlers,” said Babe, as he reined in beside him. “He wanted to come along—did for a fact, and him nearly seventy. He’d push the lid off his coffin and climb out at his own funeral if somebody’d happen to mention that thieves was brandin’ his calves.”

“You said you had started to the ranch to see me.”

“Oh, yes—I forgot. Your father sent word to the Colonel that he was sellin’ off his cattle and goin’ into sheep, and wanted the Colonel to let you know.”

“The poor old Governor! It’ll about break his heart, I know; and I should be there. At his time of life it’s a pretty hard and galling thing to quit cattle—to be forced out of the business into sheep. It’s like bein’ made to change your politics or religion against your will.”

“’Fore I’d wrangle woolers,” declared Babe, “I’d hold up trains or rob dudes or do ’most any old thing. Say, I’ve rid by sheep-wagons when I was durn near starvin’ ruther than eat with a sheep-herder or owe one a favor. Where do you find a man like the Colonel in sheep?” demanded Babe. “You don’t find ’em. Nothin’ but a lot of upstart sheep-herders, that’s got rich in five years and don’t know how to act.”

“Oh, you’re prejudiced, Babe. Not all sheepmen are muckers any more than all cattlemen are gentlemen.”

“I’m not prejudiced a-tall!” declared Babe excitedly. “I’m perfectly fair and square. Woolers is demoralizin’. Associate with woolers, and it takes the spirit out of a feller quicker’n cookin.’ In five years you won’t be half the man you are now if you go into sheep. I’ll sure hate to see it!” His voice was all but pathetic as he contemplated Ralston’s downfall.

“I think you will, though, Babe, if I get out of this with a whole hide.”

“You’ll be so well fixed you can git married then?” There was some constraint in Babe’s tone, which he meant to be casual.

Ralston’s heart gave him a twinge of pain.

“I s’pose you’ve had every chance to git acquainted with the Schoolmarm,” he observed, since Ralston did not reply.

“She doesn’t like me, Babe.”

“What!” yelled Babe, screwing up his face in a grimace of surprise and unbelief.

“She would rather talk to Ling than to me—at least, she seems far more friendly to any one else than to me.”

“Say, she must be loony not to like you!”

Ralston could not help laughing outright at Babe’s vigorous loyalty.

“It’s not necessarily a sign of insanity to dislike me.”

“She doesn’t go that far, does she?” demanded Babe.

“Sometimes I think so.”

“You don’t care a-tall, do you?”

“Yes,” Ralston replied quietly; “I care a great deal. It hurts me more than I ever was hurt before; because, you see, Babe, I never loved a woman before.”

“Aw-w-w,” replied Babe, in deepest sympathy.

Smith had congratulated himself often during the day upon the fact that he could not have chosen a more propitious time for the execution of his plans—at least, so far as the Bar C outfit was concerned. His uneasiness passed as the protecting darkness fell without their having seen a single person the entire day.

When the last glimmer of daylight had faded, Tubbs and Smith started on the drive, heading the cattle direct for their destination. They were fatter than Smith had supposed, so they could not travel as rapidly as he had calculated, but he and Tubbs pushed them along as fast as they could without overheating them.

The darkness, which gave Smith courage, made Tubbs nervous. He swore at the cattle, he swore at his horse, he swore at the rocks over which his horse stumbled; and he constantly strained his roving eyes to penetrate the darkness for pursuers. Every gulch and gully held for him a fresh terror.

“Gee! I wisht I was out of this onct!” burst from him when the howl of a wolf set his nerves jangling.

“What’d you say?” Smith stopped in the middle of a song he was singing.

“I said I wisht I was down where the monkeys are throwin’ nuts! I’m chilly,” declared Tubbs.

“Chilly? It’s hot!”

Smith was light-hearted, sanguine. He told himself that perhaps it was as well, after all, that the hold-ups had got off with the “old woman’s” money. She might have made trouble when she found that he meant to go or had gone with Dora.

“You can’t tell about women,” Smith said to himself. “They’re like ducks: no two fly alike.”

He felt secure, yet from force of habit his hand frequently sought his cartridge-belt, his rifle in its scabbard, his six-shooter in the holster under his arm. And while he serenely hummed the songs of the dance-halls and round-up camps, two silent figures, so close that they heard the clacking of the cattle’s split hoofs, Tubbs’s vacuous oaths, Smith’s contented voice, were following with the business-like persistency of the law.

The four mounted men rode all night, speaking seldom, each thinking his own thoughts, dreaming his own dreams. Not until the faintest light grayed the east did the pursuers fall behind.

“We’re not more’n a mile to water now”—Smith had made sure of his country this time—“and we’ll hold the cattle in the brush and take turns watchin’.”

“It’s a go with me,” answered Tubbs, yawning until his jaws cracked. “I’m asleep now.”

Ralston and Babe knew that Smith would camp for several hours in the creek-bottom, so they dropped into a gulch and waited.

“They’ll picket their horses first, then one of them will keep watch while the other sleeps. Very likely Tubbs will be the first guard, and, unless I’m mistaken, Tubbs will be dead to the world in fifteen minutes—though, maybe, he’s too scared to sleep.” Ralston’s surmise proved to be correct in every particular.

After they had picketed their horses, Smith told Tubbs to keep watch for a couple of hours, while he slept.

“Couldn’t we jest switch that programme around?” inquired Tubbs plaintively. “I can’t hardly keep my eyes open.”

“Do as I tell you,” Smith returned sharply.

Tubbs eyed him with envy as he spread down his own and Tubbs’s saddle-blankets.

“I ain’t what you’d call ‘crazy with the heat.’” Tubbs shivered. “Couldn’t I crawl under one of them blankets with you?”

“You bet you can’t. I’d jest as lief sleep with a bull-snake as a man,” snorted Smith in disgust, and, pulling the blankets about his ears, was lost in oblivion.

“I kin look back upon times when I’ve enj’yed myself more,” muttered Tubbs disconsolately, as he paced to and fro, or at intervals climbed wearily out of the creek-bottom to look and listen.

Ralston and Babe had concealed themselves behind a cut-bank which in the rainy season was a tributary of the creek. They were waiting for daylight, and for the guard to grow sleepy and careless. With little more emotion than hunters waiting in a blind for the birds to go over, the two men examined their rifles and six-shooters. They talked in undertones, laughing a little at some droll observation or reminiscence. Only by a sparkle of deviltry in Babe’s blue eyes, and an added gravity of expression upon Ralston’s face, at moments, would the closest observer have known that anything unusual was about to take place. Yet each realized to the fullest extent the possible dangers ahead of them. Smith, they knew to be resourceful, he would be desperate, and Tubbs, ignorant and weak of will as he was, might be frightened into a kind of frenzied courage. The best laid plans did not always work out according to schedule, and if by any chance they were discovered, and the thieves reached their guns, the odds were equal. But it was not their way to talk of danger to themselves. That there was danger was a fact, too obvious to discuss, but that it was no hindrance to the carrying out of their plans was also accepted as being too evident to waste words upon.

While the east grew pink, they talked of mutual acquaintances, of horses they had owned, of guns and big game, of dinners they had eaten, of socks and saddle blankets that had been stolen from them in cow outfits—the important and trivial were of like interest to these old friends waiting for what, as each well knew, might be their last sunrise.

Ralston finally crawled to the top of the cut-bank and looked cautiously about.

“It’s time,” he said briefly.

“Bueno.” Babe gave an extra twitch to the silk handkerchief knotted about his neck, which, with him, signified a readiness for action.

He joined Ralston at the top of the cut-bank.

“Not a sign!” he whispered. “Looks like you and me owned the world, Dick.”

“We’ll lead the horses a little closer, in case we need them quick. Then, we’ll keep that bunch of brush between us and them, till we get close enough. You take Tubbs, and I’ll cover Smith—I want that satisfaction,” he added grimly.

It was a typical desert morning, redolent with sage, which the night’s dew brought out strongly. The pink light changing rapidly to crimson was seeking out the draws and coulees where the purple shadows of night still lay. The only sound was the cry of the mourning doves, answering each other’s plaintive calls. And across the panorama of yellow sand, green sage-brush, burning cactus flowers, distant peaks of purple, all bathed alike in the gorgeous crimson light of morning, two dark figures crept with the stealthiness of Indians.

From behind the bush which had been their objective-point they could hear and see the cattle moving in the brush below; then a horse on picket snorted, and as they slid quietly down the bank they heard a sound which made Babe snicker.

“Is that a cow chokin’ to death,” he whispered, “or one of them cherubs merely sleepin’?”

In sight of the prone figures, they halted.

Smith, with his hat on, his head pillowed on his saddle, was rolled in an old army blanket; while Tubbs, from a sitting position against a tree, had fallen over on the ground with his knees drawn to his chin. His mouth, from which frightful sounds of strangulation were issuing, was wide open, and he showed a little of the whites of his eyes as he slumbered.

“Ain’t he a dream?” breathed Babe in Ralston’s ear. “How I’d like a picture of that face to keep in the back of my watch!”

Smith’s rifle was under the edge of his blanket, and his six-shooter in its holster lay by his head; but Tubbs, with the carelessness of a green hand and the over-confidence which had succeeded his nervousness, had leaned his rifle against a tree and laid his six-shooter and cartridge-belt in a crotch.

Ralston nodded to Babe, and simultaneously they raised their rifles and viewed the prostrate forms along the barrels.

“Put up your hands, men!”

The quick command, sharp, stern, penetrated the senses of the men inert in heavy sleep. Instantly Smith’s hand was upon his gun. He had reached for it instinctively even before he sat up.

“Drop it!” There was no mistaking the intention expressed in Ralston’s voice, and the gun fell from Smith’s hand.

The red of Smith’s skin changed to a curious yellow, not unlike the yellow of the slicker rolled on the back of his saddle. Panic-stricken for the moment, he grinned, almost foolishly; then his hands shot above his head.

A line of sunlight dropped into the creek-bottom, and a ray was caught by the deputy’s badge which shone on Ralston’s breast. The glitter of it seemed to fascinate Smith.

“You”—he drawled a vile name. “I orter have known!”

Still dazed with sleep, and not yet comprehending anything beyond the fact that he had been advised to put up his hands, and that a stranger had drawn an uncommonly fine bead on the head which he was in honor bound to preserve from mutilation, Tubbs blinked at Babe and inquired peevishly:

“What’s the matter with you?” He had forgotten that he was a thief.

“Shove up your hands!” yelled Babe.

With an expression of annoyance, Tubbs did as he was bid, but dropped them again upon seeing Ralston.

“Oh, hello!” he called cheerfully.

“Put them hands back!” Babe waved his rifle-barrel significantly.

“What’s the matter with you, feller?” inquired Tubbs crossly. Though he now recollected the circumstances under which they were found, Ralston’s presence robbed the situation of any seriousness for him. It did not occur to Tubbs that any one who knew him could possibly do him harm.

“Keep your hands up, Tubbs,” said Ralston curtly, “and, Babe, take the guns.”

“What for a josh is this anyhow?”—in an aggrieved tone. “Ain’t we all friends?”

“Shut up, you idjot!” snapped Smith irritably. His glance was full of malevolence as Babe took his guns. The yellow of his skin was now the only sign by which he betrayed his feelings. To all other appearances, he was himself again—insolent, defiant.

When it thoroughly dawned upon Tubbs that they were cornered and under arrest, he promptly went to pieces. He thrust his hands so high above his head that they lifted him to tiptoe, and they shook as with palsy.

“Stack the guns and get our horses, Babe,” said Ralston.

“Mine’s hard for a stranger to ketch,” said Smith surlily. “I’ll get him, for I don’t aim to walk.”

“All right; but don’t make any break, Smith,” Ralston warned.

“I’m not a fool,” Smith answered gruffly.

Ralston’s face relaxed as Smith sauntered toward his horse. He was glad that they had been taken without bloodshed, and, now the prisoners’ guns had been removed, that possibility was passed.

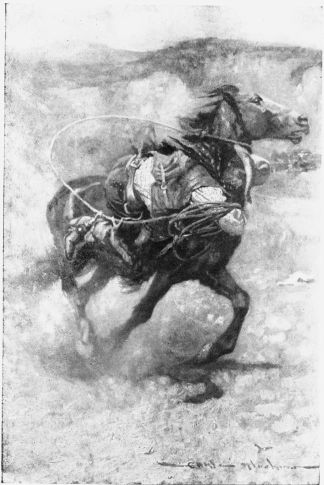

Smith’s horse was a newly broken bronco, and he was a wild beggar, as Smith had said; but he talked to him reassuringly as the horse jumped to the end of his picket-rope and stood snorting and trembling in fright, and finally laid his hand upon his neck and back. The fingers of one hand were entwined in the horse’s mane, and suddenly, with a cat-like spring made possible only by his desperation, Smith landed on the bronco’s back. With a yell of defiance which Ralston and Babe remembered for many a day, he kicked the animal in the ribs, and, as it reared in fright, it pulled loose from the picket-stake. Smith reached for the trailing rope, and they were gone!

Ralston shot to cripple the horse, but almost with the flash they were around the bend of the creek and out of sight. The breathless, speechless seconds seemed minutes long before he heard Babe coming.

“Aw-w-w!” roared that person in consternation and chagrin, as he literally dragged the horses behind him.

Ralston ran to meet him, and a glance of understanding passed between them as he leaped into the saddle and swept around the bend like a whirlwind, less than thirty seconds behind Smith.

Babe knew that he must secure Tubbs before he joined in the pursuit, and he was pulling the rawhide riata from his saddle when Tubbs, inspired by Smith’s example and imbued with the hysterical courage which sometimes comes to men of his type in desperate straits, made a dash for his rifle, and reached it. He threw it to his shoulder, but, quick as he was, Babe was quicker.

SMITH REACHED FOR THE TRAILING ROPE AND THEY WERE GONE!

With the lightning-like gesture which had made his name a byword where Babe himself was unknown, he pulled his six-shooter from its holster and shot Tubbs through the head. He fell his length, like a bundle of blankets, and, even as he dropped, Babe was in the saddle and away.

It was a desperate race that was on, between desperate men; for if Smith was desperate, Ralston was not less so. Every fibre of his being was concentrated in the determination to recapture the man who had twice outwitted him. The deputy sheriff’s reputation was at stake; his pride and self-respect as well; and the blood-thirst was rising in him with each jump of his horse. Every other emotion paled, every other interest faded, beside the intensity of his desire to stop the man ahead of him.

Smith knew that he had only a chance in a thousand. He had seen Ralston with a six-shooter explode a cartridge placed on a rock as far away as he could see it, and he was riding the little brown mare whose swiftness Smith had reason to remember.

But he had the start, his bronco was young, its wind of the best, and it might have speed. The country was rough, Ralston’s horse might fall with him. So long as Smith was at liberty there was a fighting chance, and as always, he took it.

The young horse, mad with fright, kept to the serpentine course of the creek-bottom, and Ralston, on the little mare, sure-footed and swift as a jack-rabbit, followed its lead.

The race was like a steeple-chase, with boulders and brush and fallen logs to be hurdled, and gullies and washouts to complicate the course. And at every outward curve the pin-n-gg! of a bullet told Smith of his pursuer’s nearness. Lying flat on the barebacked horse, he hung well to the side until he was again out of sight. The lead plowed up the dirt ahead of him and behind him, and flattened itself against rocks; and at each futile shot Smith looked over his shoulder and grinned in derision, though his skin had still the curious yellowness of fear.

The race was lasting longer than Smith had dared hope. It began to look as if it were to narrow to a test of endurance, for although Ralston’s shots missed by only a hair’s breadth at times, still, they missed. If Smith ever had prayed, he would have prayed then; but he had neither words nor faith, so he only hoped and rode.

A flat came into sight ahead and a yell burst from Ralston—a yell that was unexpected to himself. A wave of exultation which seemed to come from without swept over him. He touched the mare with the spur, and she skimmed the rocks as if his weight on her back were nothing. It was smoother, and he was close enough now to use his best weapon. He thrust the empty rifle into its scabbard, and shot at Smith’s horse with his six-shooter. It stumbled; then its knees doubled under it, and Smith turned in the air. The game was up; Smith was afoot.

He picked up his hat and dusted his coat-sleeve while he waited, and his face was yellow and evil.

“That was a dum good horse,” was Babe’s single comment as he rode up.

“Get back to camp!” said Ralston peremptorily, and Smith, in his high-heeled, narrow-soled boots, stumbled ahead of them without a word.

He looked at Tubbs’s body without surprise. Sullen and surly, he felt no regret that Tubbs, braggart and fool though he was, was dead. Smith had no conscience to remind him that he himself was responsible.

Babe shook out Smith’s blue army blanket and rolled Tubbs in it. Smith had bought it from a drunken soldier, and he had owned it a long time. It was light and almost water-proof; he liked it, and he eyed Babe’s action with disfavor.

“I reckon this gent will have to spend the day in a tree,” said Babe prosaically.

“Couldn’t you use no other blanket nor that?” demanded Smith.

It was the first time he had spoken.

“Don’t take on so,” Babe replied comfortingly. “They furnish blankets where you’re goin’.”

He went on with his work of throwing a hitch around Tubbs with his picket-rope.

Ralston divided the scanty rations which Smith and Tubbs, and he and Babe, had brought with them. He made coffee, and handed a cup to Smith first. The latter arose and changed his seat.

“I never could eat with a corp’ settin’ around,” he said disagreeably.

Smith’s fastidiousness made Babe’s jaw drop, and a piece of biscuit which had made his cheek bulge inadvertently rolled out, but was skillfully intercepted before it reached the ground.

“I hope you’ll excuse us, Mr. Smith,” said Babe, bowing as well as he could sitting cross-legged on the ground. “I hope you’ll overlook our forgittin’ the napkins and toothpicks.”

When they had finished, they slung Tubbs’s body into a tree, beyond the reach of coyotes. The cattle they left to drift back to their range. Tubbs’s horse was saddled for Smith, and, with Ralston holding the lead rope and Babe in the rear, the procession started back to the ranch.

Smith had much time to think on the homeward ride. He based his hopes upon the Indian woman. He knew that he could conciliate her with a look. She was resourceful, she had unlimited influence with the Indians, and she had proven that she was careless of her own life where he was concerned. She was a powerful ally. The situation was not so bad as it had seemed. He had been in tighter places, he told himself, and his spirits rose as he rode. Without the plodding cattle, they retraced their steps in half the time it had taken them to come, and it was not much after midday when they were sighted from the MacDonald ranch.

The Indians that Smith had missed were at the ford to meet them: Bear Chief, Yellow Bird, Running Rabbit, and others, who were strangers to him. They followed as Ralston and Babe rode with their prisoner up the path to put him under guard in the bunk-house.

Susie, McArthur, and Dora were at the door of the ranch-house, and Susie stepped out and stopped them when they would have passed.

“You can’t take him there; that place is for our friends. There’s the harness-house below. The dogs sleep there. There’ll be room for one more.”

The insult stung Smith to the quick.

“What you got to say about it? Where’s your mother?”

With narrowed eyes she looked for a moment into his ugly visage, then she laid her hand upon the rope and led his horse close to the open window of the bedroom.

“There,” and she pointed to the still figure on its improvised bier. “There’s my mother!”

Smith looked in silence, and once more showed by his yellowing skin the fear within him. The avenue of escape upon which he had counted almost with certainty, was closed to him. At that moment the harsh, high walls of the penitentiary loomed close; the doors looked wide open to receive him; but, after an instant’s hesitation, he only shrugged his shoulders and said:

“Hell! I sleeps good anywhere.”

In deference to Susie’s wishes, Ralston and Babe had swung their horses to go back down the path when Smith turned in his saddle and looked at Dora. She was regarding him sorrowfully, her eyes misty with disappointment in him; and Smith misunderstood. A rush of feeling swept over him, and he burst out impulsively:

“Don’t go back on me! I done it for you, girl! I done it to make our stake!”

Dora stood speechless, bewildered, confused under the astonished eyes upon her. She was appalled by the light in which he had placed her; and while the others followed to the harness-house below, she sank limply upon the door-sill, her face in her hands.

Smith sat on a wagon-tongue, swinging his legs, while they cleaned out the harness-house a bit for his occupancy.

“Throw down some straw and rustle up a blanket or two,” said Babe; and McArthur pulled his saddle-blankets apart to contribute the cleanest toward Smith’s bed.

Something in the alacrity the “bug-hunter” displayed angered Smith. He always had despised the little man in a general way. He uncinched his saddle on the wrong side; he clucked at his horse; he removed his hat when he talked to women; he was a weak and innocent fool to Smith, who lost no occasion to belittle him. Now, when the prisoner saw him moving about, free to go and come as he pleased, while he, Smith, was tied like an unruly pup, it, of a sudden, made his gorge rise; and, with one of his swift, characteristic transitions of mood, Smith turned to the Indians who guarded him.

“You never could find out who killed White Antelope—you smart-Alec Injuns!” he sneered contemptuously. “And you’ve always wanted to know, haven’t you?” He eyed them one by one. “Why, you don’t know straight up, you women warriors! I’ve a notion to tell you who killed White Antelope—just for fun—just because I want to laugh, me—Smith!”

The Indians drew closer.

“You think you’re scouts,” he went on tauntingly, “and you never saw White Antelope’s blanket right under your nose! Put it back, feller”—he nodded at McArthur. “I don’t aim to sleep on dead men’s clothes!”

The Indians looked at the blanket, and at McArthur, whom they had grown to like and trust. They recognized it now, and in the corner they saw the stiff and dingy stain, the jagged tell-tale holes.

McArthur mechanically held it up to view. He had not the faintest recollection where it had been purchased, or of whom obtained. Tubbs always had attended to such things.

No one spoke in the grave silence, and Smith leered.

“I likes company,” he said. “I’m sociable inclined. Put him in the dog-house with me.”

Susie had listened with the Indians; she had looked at the blanket, the stain, the holes; she saw the blank consternation in McArthur’s face, the gathering storm in the Indians’ eyes. She stepped out a little from the rest.

“Mister Smith!” she said. “Mister Smith”—with oily, sarcastic emphasis—“how did you know that was White Antelope’s blanket, when you never sawWhite Antelope?”