II

ON THE ALKALI HILL

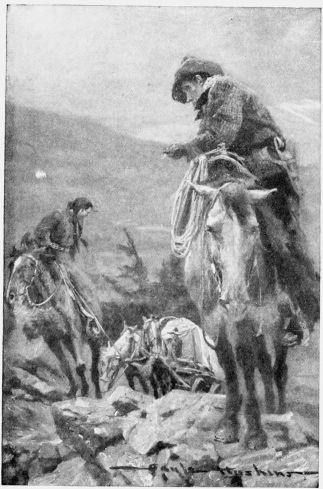

There was at least an hour and a half of daylight left when Smith struck a wagon-road. He looked each way doubtfully. The woman’s house was quite as likely to be to the right as to the left; there was no way of telling. While he hesitated, his horse lifted its ears. Smith also thought he heard voices. Swinging his horse to the right, he rode to the edge of the bench where the road made a steep and sudden drop.

At the bottom of the hill he saw a driver on the spring-seat of a round-up wagon urging two lean-necked and narrow-chested horses up the hill. They were smooth-shod, and, the weight of the wagon being out of all proportion to their strength, they fell often in their futile struggles. At the side of the road near the top of the hill the water oozed from an alkali spring, which kept the road perpetually muddy. The horses were straining every nerve and muscle, their eyes bulging and nostrils distended, and still the driver, loudmouthed and vacuously profane, lashed them mercilessly with the stinging thongs of his leather whip. Smith, from the top of the hill, watched him with a sneer on his face.

“He drives like a Missourian,” he muttered.

He could have helped the troubled driver, knowing perfectly well what to do, but it would have entailed an effort which he did not care to make. It was nothing to him whether the round-up wagon got up the hill that night—or never.

Smith thought the driver was alone until he began to back the team to rush the hill once more. Then he heard angry exclamations coming from the rear of the wagon—exclamations which sounded not unlike the buzzing of an enraged bumble-bee. He stretched his neck and saw that which suggested an overgrown hoop-snake rolling down the hill. At the bottom a little mud-coated man stood up. The part of his face that was visible above his beard was pale with anger. His brown eyes gleamed behind mud-splashed spectacles.

“Oscar Tubbs,” he demanded, “why did you not tell me that you were about to back the wagon?”

“I would have did it if I had knowed myself that the team were goin’ to back,” replied Tubbs, in the conciliatory tone of one who addresses the man who pays him his wages.

The man in spectacles groaned. “Three inexcusable errors in one sentence. Oscar Tubbs, you are hopeless!”

“Yep,” replied that person resignedly; “nobody never could learn me nothin’. Onct I knowed——”

“Stop! We have no time for a reminiscence. Have you any reason to believe that we can get up this hill to-night?”

“No chanst of it. These buzzard-heads has drawed every poun’ they kin pull. But I has some reason to believe that if you don’t hist your hoofs out’n that mud-hole, you’ll bog down. You’re up to your pant-leg now. Onct I knowed——”

The little man threw out his hand in a restraining gesture, and Tubbs, foiled again, closed his lips and watched his employer stand back on one leg while he pulled the other out of the mud with a long, sucking sound.

“What for an outfit is that, anyhow?” mused Smith, watching the proceedings with some interest. “He looks like one of them bug-hunters. He’s got a pair of shoulders on him like a drink of water, and his legs look like the runnin’-gears of a katydid.”

So intently were they all engaged in watching the man’s struggles that no one observed a girl on a galloping horse until she was almost upon them. She sat her sturdy, spirited pony like a cowboy. She was about sixteen, with a suggestion of boyishness in her appearance. Her brown hair, worn in a single braid, was bleached to a lighter shade on top, as if she rode always with bared head. Her eyes were gray, in curious contrast to a tawny skin. She was slight to scrawniness, and, one might have thought, insufficiently clad for the time of year.

“Bogged down, pardner?” she inquired in a friendly voice, as she rode up behind and drew rein. “I’ve been in that soap-hole myself. Here, ketch to my pommel, and I’ll snake you out.”

Smiling dubiously he gripped the pommel. The pony had sunk to its knees, and as it leaped to free itself the little man’s legs fairly snapped in the air.

“I thank you, Miss,” he said, removing his plaid travelling cap as he dropped on solid ground. “That was really quite an adventure.”

“This mud is like grease,” said the girl.

“Onct I knowed some mud——” began the driver, but the little man, ignoring him, said:

“We are in a dilemma, Miss. Our horses seem unable to pull our wagon up the hill. Night is almost upon us, and our next camping spot is several miles beyond.”

“This is the worst grade in the country,” replied the girl. “A team that can haul a load up here can go anywhere. What’s the matter with that fellow up there? Why don’t he help?”—pointing to Smith.

“He has made no offer of assistance.”

“He must be some Scissor-Bill from Missouri. They all act like that when they first come out.”

“Onct some Missourians I knowed——”

“Oscar Tubbs, if you attempt to relate another reminiscence while in my employ, I shall make a deduction from your wages. I warn you—I warn you in the presence of this witness. My overwrought nerves can endure no more. Between your inexpiable English and your inopportune reminiscences, I am a nervous wreck!” The little man’s voice ended on high C.

“All right, Doc, suit yourself,” replied Tubbs, temporarily subdued.

“And in Heaven’s name, I entreat, I implore, do not call me ‘Doc’!”

“Sorry I spoke, Cap.”

The little man threw up both hands in exasperation.

“Say, Mister,” said the girl curtly to Tubbs, “if you’ll take that hundred and seventy pounds of yourn off the wagon and get some rocks and block the wheels, I guess my cayuse can help some.” As she spoke, she began uncoiling the rawhide riata which was tied to her saddle.

“I appreciate the kindness of your intentions, Miss, but I cannot permit you to put yourself in peril.” The little man was watching her preparations with troubled eyes.

“No peril at all. It’s easy. Croppy can pull like the devil. Wait till you see him lay down on the rope. That yap up there at the top of the hill could have done this for you long ago. Here, Windy”—addressing Tubbs—“tie this rope to the X, and make a knot that will hold.”

“SHE’S A GAME KID, ALL RIGHT,” SAID SMITH TO HIMSELF AT THE TOP OF THE HILL.

The girl’s words and manner inspired confidence. Interest and relief were in the face of the little man standing at the side of the road.

“Now, Windy, hand me the rope. I’ll take three turns around my saddle-horn, and when I say ’go’ you see that your team get down in their collars.”

“She’s a game kid, all right,” said Smith to himself at the top of the hill.

When the sorrel pony at the head of the team felt the rope grow taut on the saddle-horn, it lay down to its work. The grit and muscle of a dozen horses seemed concentrated in the little cayuse. It pulled until every vein and cord in its body appeared to stand out beneath its skin. It lay down on the rope until its chest almost touched the ground. There was a look of determination that was almost human in its bright, excited eyes as it strained and struggled on the slippery hillside with no word of urging from the girl. She was standing in one stirrup, one hand on the cantle, the other on the pommel, watching everything with keen eyes. She issued orders to Tubbs like a general, telling him when to block the wheels, when to urge the exhausted team to greater efforts, when to relax. Nothing escaped her. She and the little sorrel knew their work. As the man at the roadside watched the gallant little brute struggle, literally inch by inch, up the terrible grade he felt himself choking with excitement and making inarticulate sounds. At last the rear wheels of the wagon lurched over the hill and stood on level ground, while the horses, with spreading legs and heaving sides, gasped for breath.

“Awful tired, ain’t you, Mister?” the girl asked dryly, of the stranger on horseback, as she recoiled her rope with supple wrist and tied it again to the saddle by the buckskin thongs.

“Plumb worn to a frazzle,” Smith replied with cool impudence, as he looked her over in much the same manner as he would have eyed a heifer on the range. “I was whipped for working when I was a boy, and I’ve always remembered.”

“It must be quite a ride—from the brush back there in Missouri where you was drug up.”

“I ranges on the Sundown slope,” he replied shortly.

“They have sheep-camps over there, then?”

Again the slurring insinuation pricked him.

“Oh, I can twist a rope and ride a horse fast enough to keep warm.”

“So?”—the inflection was tantalizing. “Was that horse gentled for your grandmother?”

He eyed her angrily, but checked the reply on his tongue.

“Say, girl, can you tell me where I can find that fat Injun woman’s tepee who lives around here?”

“You mean my mother?”

He looked at her with new interest.

“Does she live in a log cabin on a crick?”

“She did about an hour ago.”

“Is your mother a widder?”

“Lookin’ for widders?”

“I likes widders. It happens frequent that widders are sociable inclined—especially if they are hard up,” he added insolently.

“Oh, you’re ridin’ the grub-line?” Her insolence equalled his own.

“Not yet;” and he took from his pocket a thick roll of banknotes.

“Blood money? Some sheep-herder’s month’s pay, I guess.”

“You’re a good guesser.”

“Not very—you’re easy.”

The girl’s dislike for Smith was as unreasoning and violent as was her liking for the excitable little man whom she had helped up the hill, and whose wagon was now rumbling close at her horse’s heels.

They all travelled together in silence until, after a mile and a half on the flat, the road sloped gradually toward a creek shadowed by willows. On the opposite side of the creek were a ranch-house, stables, and corrals, the extent of which brought a glint of surprise to Smith’s eyes.

“That’s where the widder lives who might be sociable inclined if she was hard up,” said the girl, with a sneer which made Smith’s fingers itch to choke her. “Couldn’t coax you to stop, could I?”

“I aims to stay,” Smith replied coolly.

“Sure—it won’t cost you nothin’.”

The girl waited for the wagon, and, with a change of manner in marked contrast to her impudent attitude toward Smith, invited the little man to spend the night at the ranch.

“We should not be intruders?” he asked doubtfully.

“You won’t feel lonesome,” she answered with a laugh. “We keep a kind of free hotel.”

“Colonel, I cakalate we better lay over here,” broke in Tubbs.

His employer winced at this new title, but nodded assent; so they all forded the shallow stream and entered the dooryard together.

“Mother!” called the girl.

One of the heavy plank doors of the long log-house opened, and a short woman, large-hipped, full-busted—in appearance a typical blanket squaw—stood in the doorway. Her thick hair was braided Indian fashion, her fingers adorned with many rings. The wide girdle about her waist was studded with brass nail-heads, while gaily-beaded moccasins covered her short, broad feet. Her eyes were soft and luminous, like an animal’s when it is content; but there was savage passion too in their dark depths.

“This is my mother,” said the girl briefly. “I am Susie MacDonald.”

“My name is Peter McArthur, madam.”

The little man concealed his surprise as best he could, and bowed.

The girl, quick to note his puzzled expression, explained laconically:

“I’m a breed. My father was a white man. You’re on the reservation when you cross the crick.”

Recovering himself, the stranger said politely:

“Ah, MacDonald—that good Scotch name is a very familiar one to me. I had an uncle——”

“I go show dem where to turn de horses,” interrupted the Indian woman, to whom the conversation was uninteresting. So, without ceremony, she padded away in her moccasins, drawing her blanket squaw-fashion across her face as she waddled down the path.

At the mission the woman had obtained the rudiments of an education. There, too, she had learned to cut and make a dress, after a crude, laborious fashion, and had acquired the ways of the white people’s housekeeping. She was noted for the acumen which she displayed in disposing of the crop from her extensive hay-ranch to the neighboring white cattlemen; and MacDonald, the big, silent Scotch MacDonald who had come down from the north country and married her before the reservation priest, was given the credit for having instilled into her some of his own shrewdness and thrift.

In the corral the Indian woman came upon Smith. He turned his head slowly and looked at her. For a second, two, three seconds, or more, they looked into each other’s eyes. His gaze was confident, masterful, compelling; hers was wondering, until finally she dropped her eyes in the submissive, modest, half-shy way of Indian women.

Smith moistened his short upper lip with the tip of his tongue, while the shadow of a smile lurked at the corner of his mouth. He turned to his saddle, again, and without speaking, she watched him until he had gone into the barn. His saddle lay on the ground, half covering his blankets. Something in this heap caught the woman’s eyes and held them. Swooping forward, she caught a protruding corner between her thumb and finger and pulled a gay, striped blanket from the rest. Lifting it to her nose, she smelled it. Smith saw the act as he came out of the door, but there was neither consternation nor fear in his face. Smith knew Indian women.