XV

WHERE A MAN GETS A THIRST

While the four stood staring blankly at the trampled earth and the thin thread of smoke rising from a smouldering stick on a bed of ashes, Smith, miles away, was watching the skyline in the direction from which he had come, and gulping coffee from a tin can. He had slept—the print of his body was still in the sand—but his sleep had been broken and brief. He had ridden fast and all night long, but he was not yet far enough away to feel secure. There was always a danger, too, that the horses would break for their home range, although he kept the mare who led the band on the picket rope when they were not travelling. His own horse, always saddled, was picketed close.

“I’ll never make a turn like this alone again,” he muttered discontentedly. “It’s too much like work to suit me, and I ain’t in shape to make a hard ride. I’ve got soft layin’ around the ranch.” He stretched his stiff muscles and made a wry face. Then he smiled. “I’d like to see that brat’s face when she comes with my grub this mornin’.” He looked off again to the skyline.

“I ketched her eyein’ me once or twice in a way that didn’t look good to me; and I had that notorious strong feelin’ take holt of me that she wasn’t on the square. I’d better be sure nor sorry;—that’s no josh. I takes no chances, me—Smith; I tips my hand to no petticoat.”

He noted with relief that the wind was rising. He was glad, for it would obliterate every print and make tracking impossible. He had kept to the rocks, as the unshod and now foot-sore horses bore evidence, but, even so, there was always a chance of tell-tale prints.

“I can take it easy after I get to water,” he told himself. “This water business is ser’ous”—he looked uneasily at the stretch of desolation ahead of him—“but unless the Injuns lied, they’s some.

“I hope the boys are to home,” he went on, “for if they are it won’t take us long to work these brands over. When they take ’em off my hands and I gets my wad, I’ll soak it away, me—Smith. I’ll hand it in at the bank, and I’ll say to the dude at the winder, ’Feller,’ I’ll say, ‘me and a little Schoolmarm are goin’ to housekeepin’ after while, so just hang on to that till I calls.’” Smith grinned appreciatively at the picture.

“His eyes will stick out till you could snare ’em with a log-chain, for I ain’t known as a marryin’ man.” His face sobered. “I’ve got to get to work and get a wad—she shot that into me straight; and she’s right. I couldn’t ask no woman like her to hang out her own wash in front of a two-roomed shack. I got to get the dinero, and between man and man, Smith, like you and me, I’m nowise particular how I gets it, so long as she don’t know. I’ll take any old chance, me—Smith. And dead men’s eyes hasn’t got the habit of follerin’ me around in the dark, like some I’ve knowed. She’d think I was a horrible feller if—but shucks! What’s done’s done.”

He lifted his arms and stretched them toward the skyline, and his voice vibrated:

“I love you, girl! I love you, and I couldn’t hurt you no more nor a baby!”

Before he coiled the picket-ropes and started the horses moving, he got down on his knees and took a mouthful of water from a lukewarm pool. He spat it upon the ground in disgust.

“That’s worse nor pizen,” he declared with a grimace. “You bet I’ve got to strike water to-day somehow. The horses won’t hardly touch this, and they’re all ga’nted up for the want of it. There ought to be water over there in some of them gulches, seems-like”—he looked anxiously at the expanse stretching interminably to the northeast—“and I’ll have to haze ’em along until we hit it.”

His tired horse seemed to sag beneath his weight as he landed heavily in the saddle; and the band of foot-sore horses, the hair of their necks and legs stiff with sweat and dust, bore little resemblance to the spirited animals that Susie had driven from the reservation. It was now no effort to keep up with them, and Smith herded them in front of him like a flock of sheep. He wondered what another day, perhaps two days more, of constant travel would do, if fifty miles or so had used them up. There was not now the fear of capture to urge him forward, but the need of reaching water was an equally great incentive to haste.

Smith travelled until late in the afternoon without an audible complaint at the intense discomforts of the day. He found no water, and he ate only a handful of sugar as he rode. He journeyed constantly toward the northeast, in which direction, he thought, must be the ranch which was his destination. At each intervening gulch a hope arose that it might contain water, but always he was disappointed. Between the alkali dust and the heat of the midday sun, which was unusually hot for the time of year, his lips were cracked and his throat dry.

“Ain’t this hell!” he finally muttered fretfully. “And no more jump in this horse nor a cow. I can do without grub, but water! Oh, Lord! I could lap up a gallon.”

The slight motion of his lips started them bleeding. He wiped the blood away on the back of his hand and continued:

“This is a reg’lar stretch of Bad Lands. If them blamed Injuns hadn’t lied, I could have packed water easy enough. They don’t seem to be no end to it, and I must have come forty mile. You’re in for it, Smith. It’s goin’ to be worse before it’s better. If I could only lay in a crick—roll in it—douse my face in it—soak my clothes in it! God! I’m dry!”

He spurred his horse, but there was no response from it. It was dead on its feet, between the hard travel of the previous day and night and another day without water. He cursed the horses ahead as they lagged and necessitated extra steps.

He rode for awhile longer, until he realized that at the snail’s pace they were moving he was making little headway. A rest would pay better in the long run, although there was some two hours of daylight left.

The dull-eyed horses stood with drooping heads, too thirsty and too tired to hunt for the straggling spears of grass and salt sage which grew sparsely in the alkali soil.

After Smith had unsaddled, he opened the grain-sack which contained his provisions. Spreading them out, he stood and eyed them with contempt.

“And I calls myself a prairie man,” he said aloud, in self-disgust. “Swine-buzzom—when I’m perishin’ of thirst! If only I’d put in a couple of air-tights. Pears is better nor anything; they ain’t so blamed sweet, they’re kind of cool, and they has juice you can drink. And tomaters—if only I had tomaters! This here dude-food, this strawberry jam, is goin’ to make me thirstier than ever. No water to mix the flour with, nothing to cook in but salt grease. Smith, you’re up against it, you are.”

He built a little sage-brush fire, over which he cooked his bacon, and with it he ate a dry biscuit, but his thirst was so great that it overshadowed his hunger. Chewing grains of coffee stimulated him somewhat, but the bacon and glucose jam increased his thirst tenfold, if such a thing were possible. His thoughts of Dora, and his dreams of the future, which had helped him through the afternoon, were no longer potent. He could now think only of his thirst—of his overpowering desire for water. It filled his whole mental horizon. Water! Water! Water! Was there anything in the world to be compared with it!

His face was deep-lined with distress as he sat by the camp-fire, trying in vain to moisten his lips with his dry tongue. One picture after another arose before him: streams of crystal water which he had forded; icy mountain springs at which he had knelt and drank; deep wells from which he had thrown whole bucketfuls away after he had quenched what he then called thirst. Thirst! He never had known thirst. What he had called thirst was laughable in comparison with this awful longing, this madness, this desire beside which all else paled.

In any other than an alkali country, the lack of water for the same length of time would have meant little more than discomfort, but the parching, drying effect of the deadly white dust entailed untold suffering upon the traveller caught unprepared as was Smith.

He rolled and smoked innumerable cigarettes, rising at intervals to pace restlessly to and fro. His lips and tongue were so parched that both taste and feeling seemed deadened. Had he not seen the smoke, it is doubtful if he could have been sure he was smoking.

He wandered away from the fire after a time, walking aimlessly, having no objective point. He desired only to be moving. Something like a half-mile from his camp he came into a shallow cut which appeared to have been made during bygone rainy seasons, but which now bore no evidence of having carried water for many years. He followed it mechanically, stumbling awkwardly in his high-heeled cowboy boots over the rocks which had washed into its bed from the alkali-coated sides. Suddenly he cried aloud, with a shrill, penetrating cry that was peculiar to him when surprised or startled. He had inadvertently kicked up a rock which showed moisture beneath it!

He began to run, with his mouth open, his bloodshot eyes wide and staring. There was a bare chance that it might come from one of those desert springs which appear and disappear at irregular intervals in the sand. As he ran, he saw hoof-tracks in what had once been mud, and his heart beat higher with hope. He had a thought in his half-crazed brain that the water might disappear before he could reach it, and he ran like one frenzied with fear. The world was swimming around him, his heart was pounding in his breast, yet still he stumbled on at top speed.

IT MEANT DEATH—BUT IT WAS WET!—IT WAS WATER!

The cut grew deeper, and indications of moisture increased. He saw a growth of large sage-brush, then a clump or two of rank, saw-edged grass. These things meant water! He turned a bend and there, beneath a high bank, was a pool crusted to the edge with alkali!

Smith knew that it was strongly alkali; that it meant certain illness—enough of it, death. But it was wet!—it was water!—and he must drink. He fell, rather than knelt, in it. When taste came back he realized that it was flat and lukewarm, but he continued to gulp it down. At any other time it would have nauseated him, but now he drank to his capacity. When he could drink no more, he sat up—realizing what he had done. He had swallowed liquid poison—nothing less. The result was inevitable. He was going to be ill—excruciatingly, terribly ill, alone in the Bad Lands! This was as certain as was the fact that night had come.

“I was so dry,” he whimpered, “I couldn’t help it! I was so dry!” He scrambled to his feet.

“I gotta get back to camp. This water’s goin’ to raise thunder when it begins to get in its work. I gotta get back to my blankets and lay down.”

Before he reached the heap of ashes which he called camp, the first symptoms of his coming agony began to show themselves. He felt slightly nauseated; then a quick, griping pain which was a forerunner of others which were to make him sweat blood.

Many of these springs and stagnant pools carry arsenic in large quantities, and of such was the water of which Smith had drunk. In his exhaustion, the poison and accompanying impurities took hold of him with a fierceness which it might not have done had he been in perfect physical condition; but his stomach, already disordered from irregular and improper food, absorbed the poison with avidity, and the result was an agony indescribable.

As he writhed on his saddle-blankets under the stars, he groaned and cursed that unknown God above him. His face and hands were covered with a cold sweat; his forehead and finger-tips were icy. The night air was chill, but he was burning with an inward fever, and his thirst now was akin to madness. With all his strength of will, he fought against his desire to return to the pool.

Smith did not expect to die. He felt that if he could keep his senses and not crawl back to drink again, he would pull through somehow. The living hell he now endured would pass.

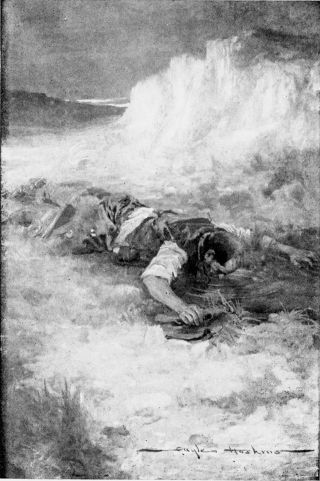

He wallowed and threshed about like a suffering animal, beating the earth with his clenched fists, during the paroxysms of cutting, wrenching pain. His suffering was supreme. All else in the world shrank into insignificance beside it. No thoughts of Dora fortified him; no mother’s face came to comfort him; nor that of any human being he had ever known. He was just Smith—self-centred—alone; just Smith, fighting and suffering and struggling for his life. His anguish found expression in the single sentence:

“I’m sick! I’m sick! Oh, God! I’m sick!” He repeated it in every key with every inflection, and his moans lost themselves in the silence of the desert.

Yet underneath it all, when his agony was at its height, he still believed in himself. In a kind of subconscious arrogance, he believed that he was stronger than Fate, more powerful than Death. He would not die; he would live because he wanted to live. Death was not for him—Smith. For others, but not for him.

At last the paroxysms became less frequent and lost their violence. When they ceased altogether, he lay limp and half-conscious. He was content to remain motionless until the flies and insects of the sand roused him to the fact that another day had come.

He was incredibly weak, and it took all his remaining strength to throw his forty-pound cow-saddle upon his horse’s back. His knees shook under him, and he had to rest before he could lift his foot to the stirrup and pull himself into the seat.

Before he rode away he turned and looked at the hollow in the sand where his blankets had been.

“That was a close squeak, Smith,” was all he said.

He had no desire for breakfast; in fact, he could not have eaten, for his tongue was swollen, and his throat felt too dry to swallow. His skin was the color of his saddle-leather, and his inflamed eye-balls had the redness of live coals. Smith was far from handsome that morning.

His own recent sufferings had in nowise made him more merciful: he spurred his stiff and lifeless horse without pity, but he spurred uselessly. It stumbled under him as he drove the spiritless band toward the hopeless waste ahead of him.

“Unless I’m turned around, we ought to get out of this to-day,” he thought. The effort of speaking aloud was too great to be made. “Unless I’m lost, or fall off my horse, we ought to make it sure.”

Distance had meant nothing to him during the first evening and night of his ride. He had fixed his eye upon the furthermost object within his range of vision and ridden for it—buoyant, confident, as his horse’s flying feet ate up the intervening miles. Now he shrank from looking ahead. He dreaded to lift his eyes to the interminable desolation stretching before him. The minutes seemed hours long; time was protracted as though he had been eating hasheesh. He felt as if he had ridden for a week, before his horse’s shadow told him that noon had come. The jar of his horse hurt him, and it all seemed unreal at times, like a torturing nightmare from which he must soon awake. He rode long distances with closed eyes as the day wore on. The world, red and wavering, swung around him, and he gripped his saddle-horn hard. The only real thing, the agony of which was too great to be mistaken for anything else, was his thirst. This was superlatively intense. There were moments when he had a desire to slide easily from his horse into the sand and lie still—just to be rid for a time of that jar that hurt him so. He viewed the distance to the ground contemplatively. It was not great. He would merely crumple up like a drunken person and go to sleep.

But these moments soon passed: the instinct of self-preservation was quick to assert itself. Each time, he took a fresh grip on the slack reins and kept his horse plodding onward, ever onward, through the heavy sand and blistering alkali dust, and always to the northeast, where somewhere there was relief which somehow he must reach.

Mile after mile crept under his horse’s lagging feet. The midday sun beat down upon him, drying the very blood in his veins, scorching him, shrivelling him, and yet there seemed no end to the waterless gulches, to the sand, the cactuses, the stunted sage-brush. His horse was stumbling oftener, but he felt no pity—only irritation that it had not more stamina. A sort of numbness, the lethargy of great weakness, was creeping over him; his heart was sagging with a dull despair. He believed that he must be lost, yet he was past cursing or complaining aloud. Only an occasional gasp or a fretful, inarticulate sound came when his horse stumbled badly.

He thought he saw a barbed wire fence. A barbed wire fence meant civilization! He swung his horse and rode toward it. The dark spots he had thought were posts were only sage-brush. The smarting of his eye-balls and eyelids aroused him to an astonishing fact: he was crying in his weakness, crying of disappointment like a child! But he was astonished most that he had tears to shed—that they had not dried up like his blood.

Tears! He remembered his last tears, and they kept on sliding down his cheek now as he recalled the occasion. His father had given him a colt back there where they slept between sheets. He had broken it himself, and taught it tricks. It whinnied to him when he passed the stable. The other boys envied him his colt, and he meant to show it at the fair. He came home one day and the colt was gone. His father handed him a silver dollar. He had thrown the money at his father and struck him in the face, and while the tears streamed from his eyes he had cursed his father with the oaths with which his father had so frequently cursed him; and he had kept on cursing until he was beaten into unconsciousness. There had been no love between them, ever, but he had not expected that. Since then there had been no time or inclination for tears, for it was then he had “quit the flat.” The rage of his boyhood came back to Smith as he thought of it now. He swore, though it hurt him to speak.

His eyes were still smarting when he raised them to see a horseman on a distant ridge. The sight roused him like a stimulant. Was he friend or foe? He reined his horse, and, drawing his rifle from its scabbard, waited; for the stranger had seen him and was riding toward him down the ridge.

“If he ain’t my kind, I’ll have to stop him,” Smith muttered.

The strength of excitement came to him, and once more he sat erect in the saddle, fingering the trigger as the horseman came steadily on.

“He rides like a Texican,” Smith thought. There was something familiar in the stranger’s outlines, the way he threw his weight in one stirrup, but Smith was taking no chances. He put out a hand in warning, and the other man stopped.

The swarthy face of the stranger wore a comprehending grin. No honest man drove horses across the Bad Lands. He threw the Indian sign of friendship to Smith, and they each advanced.

“How far to water, Clayt?”

“Well, dog-gone me! Smith!”

“How far to water?” Smith yelled the words in hoarse ferocity.

The stranger glanced at the barebacked horses, and then at the shimmering heat waves of the desert.

“Just around the ridge,” he answered. “My God, man, didn’t you pack water?”

But Smith was already out of hearing.