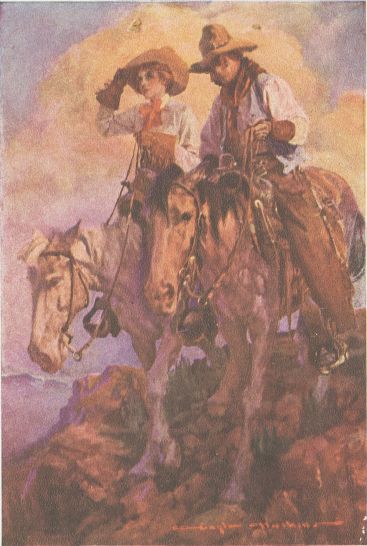

“THAT LOOK IN YOUR EYES—THAT LOOK AS IF YOU HADN’T NOTHIN’ TO HIDE—IS IT TRUE?”

I

“ME—SMITH”

A man on a tired gray horse reined in where a dim cattle-trail dropped into a gulch, and looked behind him. Nothing was in sight. He half closed his eyes and searched the horizon. No, there was nothing—just the same old sand and sage-brush, hills, more sand and sage-brush, and then to the west and north the spur of the Rockies, whose jagged peaks were white with a fresh fall of snow. The wind was chill. He shivered, and looked to the eastward. For the last few hours he had felt snow in the air, and now he could see it in the dim, gray mist—still far off, but creeping toward him.

For the thousandth time, he wondered where he was. He knew vaguely that he was “over the line”—that Montana was behind him—but he was riding an unfamiliar range, and the peaks and hills which are the guide-boards of the West meant nothing to him. So far as he knew, he was the only human being within a hundred miles. His lips drew back in a half-grin and exposed a row of upper teeth unusually white and slightly protruding. He was thinking of the meeting with the last person to whom he had spoken within twenty-four hours. He closed one eye and looked up at the sun. Yes, it was just about the same time yesterday that a dude from the English ranch, a dude in knee breeches and shiny-topped riding boots, had galloped confidently toward him. He had dismounted and pretended to be cinching his saddle. When the dude was close enough Smith had thrown down on him with his gun.

“Feller,” he had said, “I guess I’ll have to trade horses with you. And fall off quick, for I’m in kind of a hurry.”

The grin widened as he thought of the dude’s surprised eyes and the dude’s face as he dropped out of the saddle without a word. Smith had stood his victim with his hands above his head while he pulled the saddle from his horse and threw it upon his own. The dude rode a saddle with a double cinch, and the fact had awakened in the Westerner a kind of interest. He had even felt a certain friendliness for the man he was robbing.

“Feller,” he had asked, “do you come from the Mañana country?”

“From Chepstow, Monmouth County, Wales,” the dude had replied, in a shaking voice.

“Where did you get that double-rigged saddle, then?”

“Texas.”

The answer had pleased Smith.

“You ain’t losin’ none on this deal,” he had then volunteered. “This horse that you just traded for is a looker when he is rested, and he can run like hell. You can go your pile on him. Just burn out that lazy S brand and run on your own. You can hold him easy, then. I like a feller that rides a double-rigged saddle in a single-rigged country. S’long, and keep your hands up till I’m out of range.”

“Thank you,” the dude had replied feebly.

When Smith had ridden for a half a mile he had turned to look behind him. The dude was still standing with his hands high above his head.

“I wonder if he’s there yet?” The man on horseback grinned.

He reached in the pocket of his mackinaw coat and took out a handful of sugar.

“You can travel longer on it nor anything,” he muttered.

He congratulated himself that he had filled his pocket from the booze-clerk’s sugar-bowl before the mix came. The act was characteristic of him, as was the forethought which had sent him to the door to pick the best saddle-horse at the hitching-post, before the lead began to fly.

The man suddenly realized that the mist in the east was denser, and spreading. He jabbed the spurs into his horse and sent the jaded animal sliding on its fetlocks down the steep and rocky trail that led into the dry bed of a creek which in the spring flowed bank high. In the bottom he pulled his horse to its haunches and leaned from his saddle to look at a foot-print in a little patch of smooth sand no larger than his two hands. The print had been made by a moccasined foot, and recently; otherwise the wind would have wiped it out.

He threw his leg over the cantle of the saddle and stepped softly to the ground. Dropping the reins, he looked up and down the gulch. Then he drew his rifle from the scabbard and began to hunt for more tracks. As he searched, his movements were no longer those of a white man. His pantomime, stealthy, cautious, was the pantomime of the Indian. He crept up the gulch to a point where it turned sharply. His stealth became the stealth of the coyote. In spite of the leather soles and exaggerated high heels of the boots he wore his movements were absolutely noiseless.

An Indian of middle age, in blue overalls, moccasins, a limp felt hat coming far down over his braided hair, a gaily striped blanket drawn about his shoulders, stood in an attitude of listening, carelessly holding a cheap, single-barrelled shotgun. He had heard the horse sliding down the trail and was waiting for it to appear on the bench above.

The stranger took in the details of the Indian’s costume, but his eye rested longest upon the gay blanket. He might need a blanket with that snow in the air. It looked like a good blanket. It seemed to be thick and was undoubtedly warm.

The Indian saw him the instant he rose from his hiding-place behind a huge sage-brush. Startled, the red man instinctively half raised his gun. The stranger gave the sign of attention, then, touching his breast and lifting his hand slightly, told him in the sign language used by all tribes that “his heart was right”—he was a friend.

The Indian hesitated and lowered his gun, but did not advance. The stranger then asked him where he would find the nearest house, and whether it was that of a white or a red man. In swift pantomime, the Indian told him that the nearest house was the home of a “full-blood,” a woman, a fat woman, who lived five miles to the southeast, in a log cabin, on running water.

Before he turned to go, the stranger again touched his breast and raised his hand above his heart to reiterate his friendship. He took a half-dozen steps, then whirled on his heel. As he did so, he brought his rifle on a line with the Indian’s back, which was toward him. Simultaneously with the report, the Indian fell on his back on the side of the gulch. He drew up his leg, and the stranger, thinking he had raised it for a gun-rest, riddled him with bullets.

The white man’s bright blue eyes gleamed; the pupils were like pin-points. The grin which disclosed his protruding teeth was like the snarl of a dog before it snaps. The expression of the man’s face was that of animal ferocity, pure and simple. He edged up cautiously, but there was no further movement from the Indian. He had been dead when he fell. The white man gave a short laugh when he realized that the raising of the leg had been only a muscular contraction. To save the blanket from the blood which was soiling it, he tore it from the limp, unresisting shoulders, and rubbed it in the dirt to obliterate the stain. He cursed when he saw that a bullet had torn in it two jagged, tell-tale holes.

He glanced at the Indian’s moccasins, then, stooping, ripped one off. He examined it with interest. It was a Cree moccasin. The Indian was far from home. He examined the centre seam: yes, it was sewed with deer-sinew.

“The Crees can tan to beat the world,” he muttered, “but I hates the shape of the Cree moccasin. The Piegans make better.” He tossed it from him contemptuously and picked up the shotgun.

“No good.” He threw it down and straightened the Indian’s head with the toe of his boot. “I despises to lie cramped up, myself.”

Returning to his horse, he removed his saddle, and folded the Indian’s blanket inside of his own. Then he recinched his saddle, and turned his horse’s head to the southeast, where “the full-blood—the woman, the fat woman—lived in a log cabin by running water.”

He glanced over his shoulder as he spurred his horse to a gallop.

“I’m a killer, me—Smith,” he said, and grinned.